While writing the Why Java Strings Are Special post, I realized I didn’t remember exactly how stack and heap really works. So I dug out my operating system notes and refreshed some good ol’ memories.

Here we go, a deep dive into memory management in C!

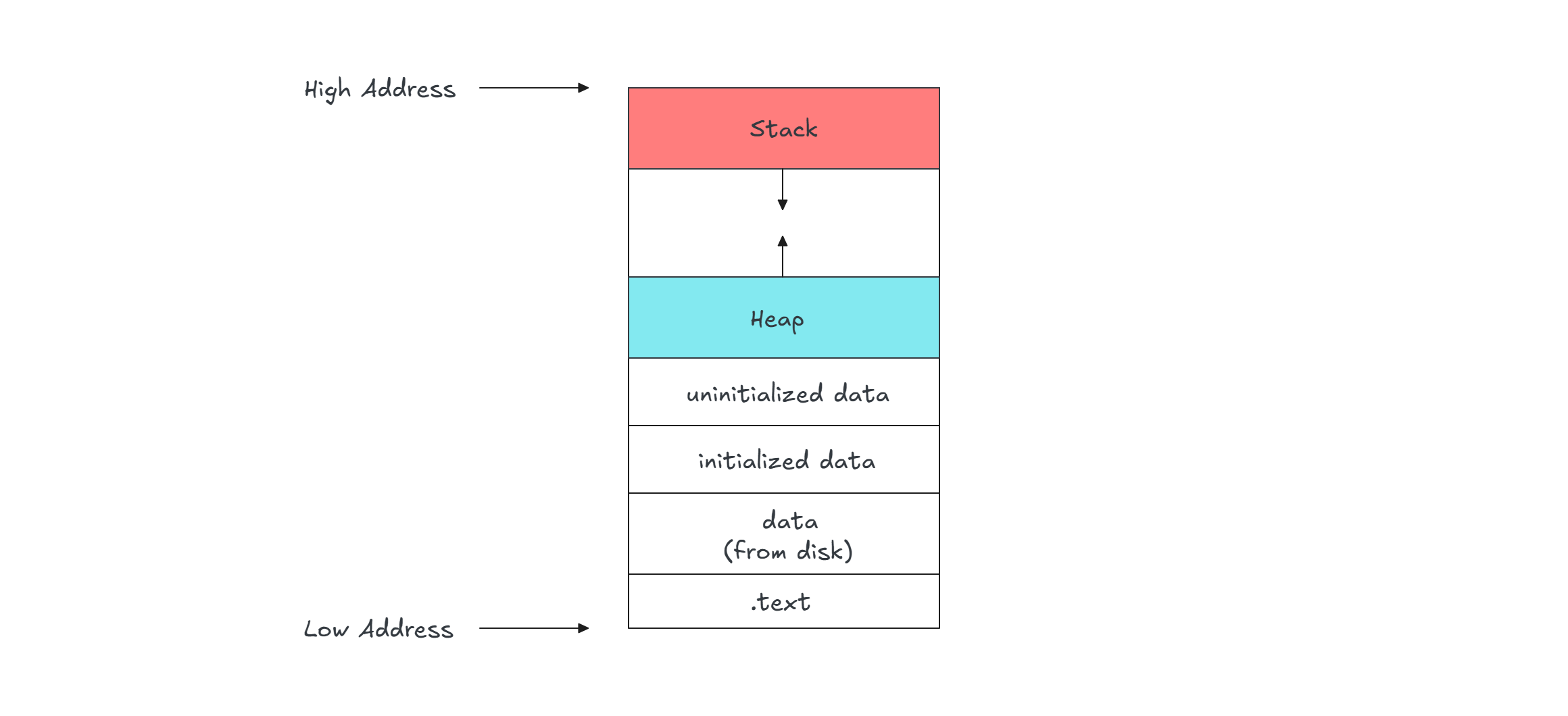

Memory layout of a C program

A C program’s memory can be visualized as follows:

The key parts are:

.text- Stores the compiled machine code (read-only).Datasection - split into:- Initialized data - Stores global and static variables with assigned values.

- Uninitialized data - Stores global and static variables without assigned values.

Stack- Stores function call frames, local variables, and grows downwards.Heap- Used for dynamic memory allocation, grows upwards.

Note: This is a simplified representation of how a program appears in memory. In reality, the Memory Management Unit (MMU) handles all address translations for virtual memory. The CPU “spits” out a logical address which is translated by the MMU into a certain segment/page then allocated in the RAM. It can be worth investigating about virtual memory in another blog post though ;)

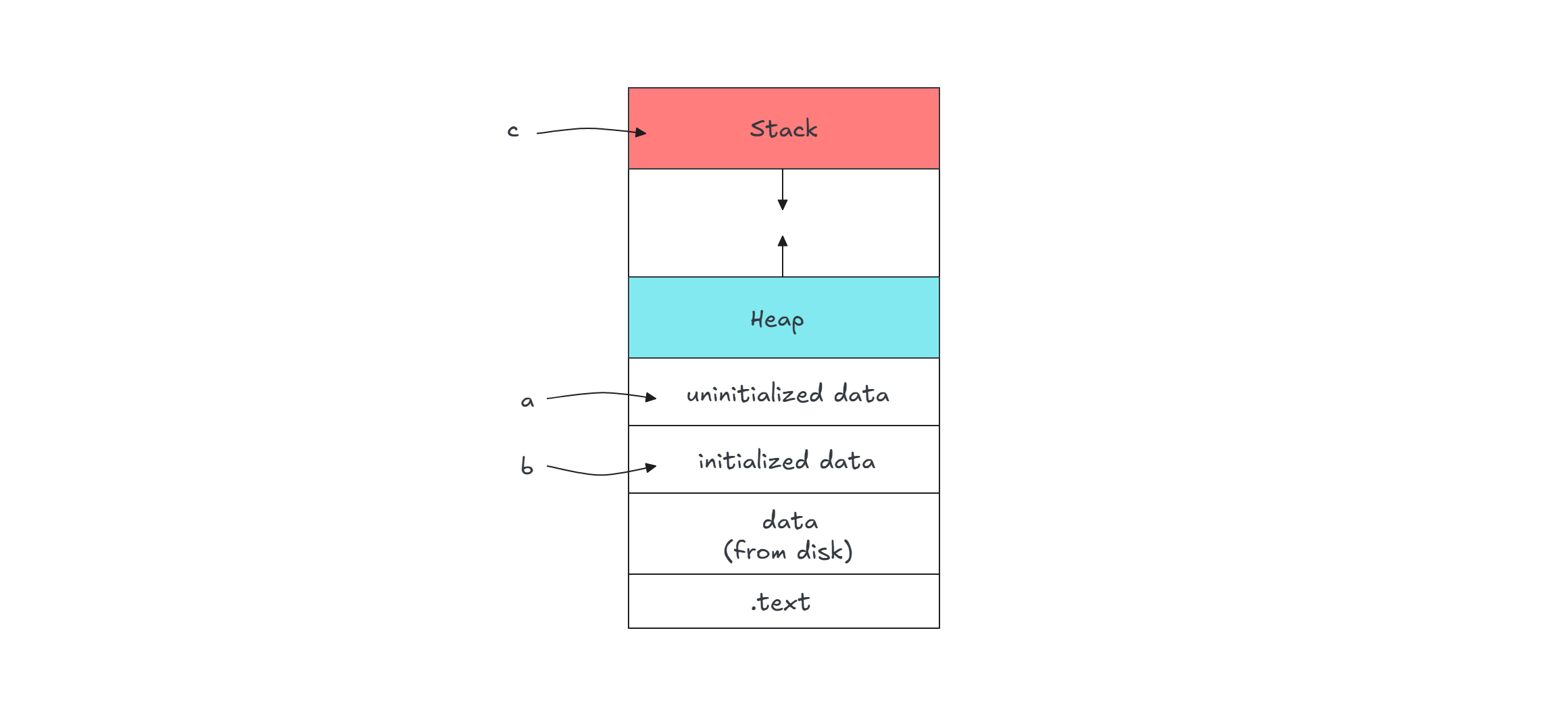

Let’s consider the following example:

int a;

int b = 10;

int main () {

int c = 10;

return 0;

}

ais an uninitialized global variable, so it goes into the uninitialized data section.bis an initialized global variable, so it is stored in the initialized data section.cis a local variable inmain(), so it is stored in the stack frame ofmain().

Allocating in stack and heap

By default, all variables are allocated on the stack.

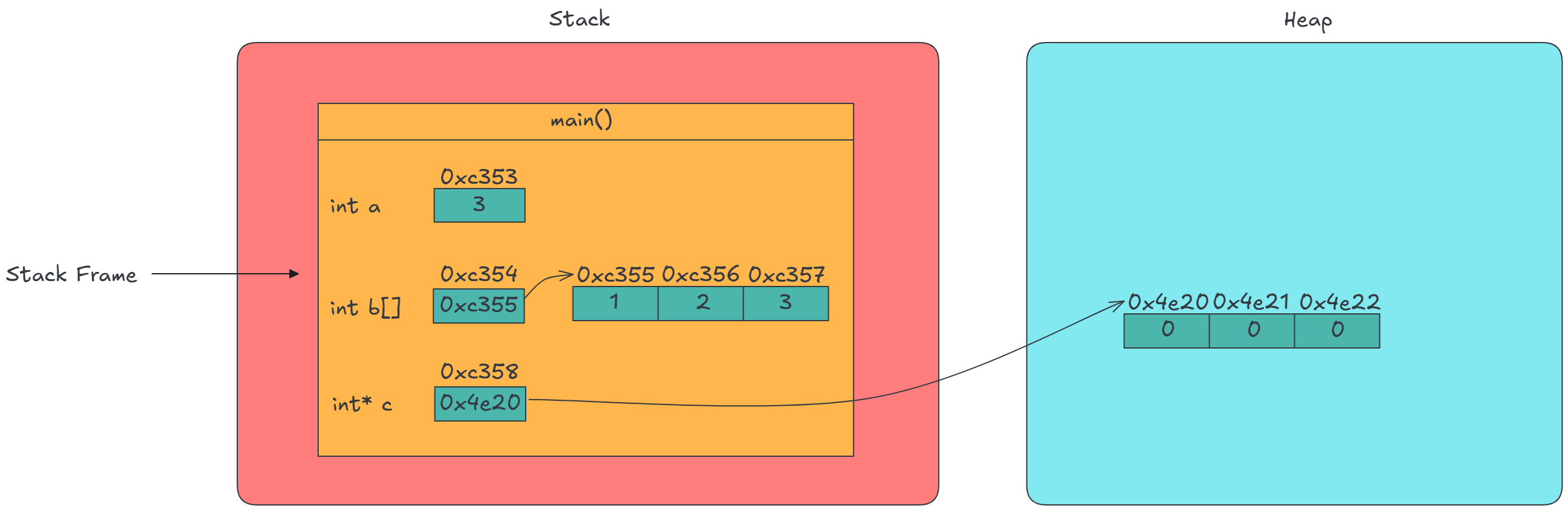

However, we can allocate memory on the heap using malloc(). Consider this example:

#include <stdlib.h>

int main() {

int a = 3; // Stored in stack

int b[] = {1, 2, 3}; // Stored in stack

int *c = malloc(sizeof(int) * 3); // Allocated in heap

return 0;

}

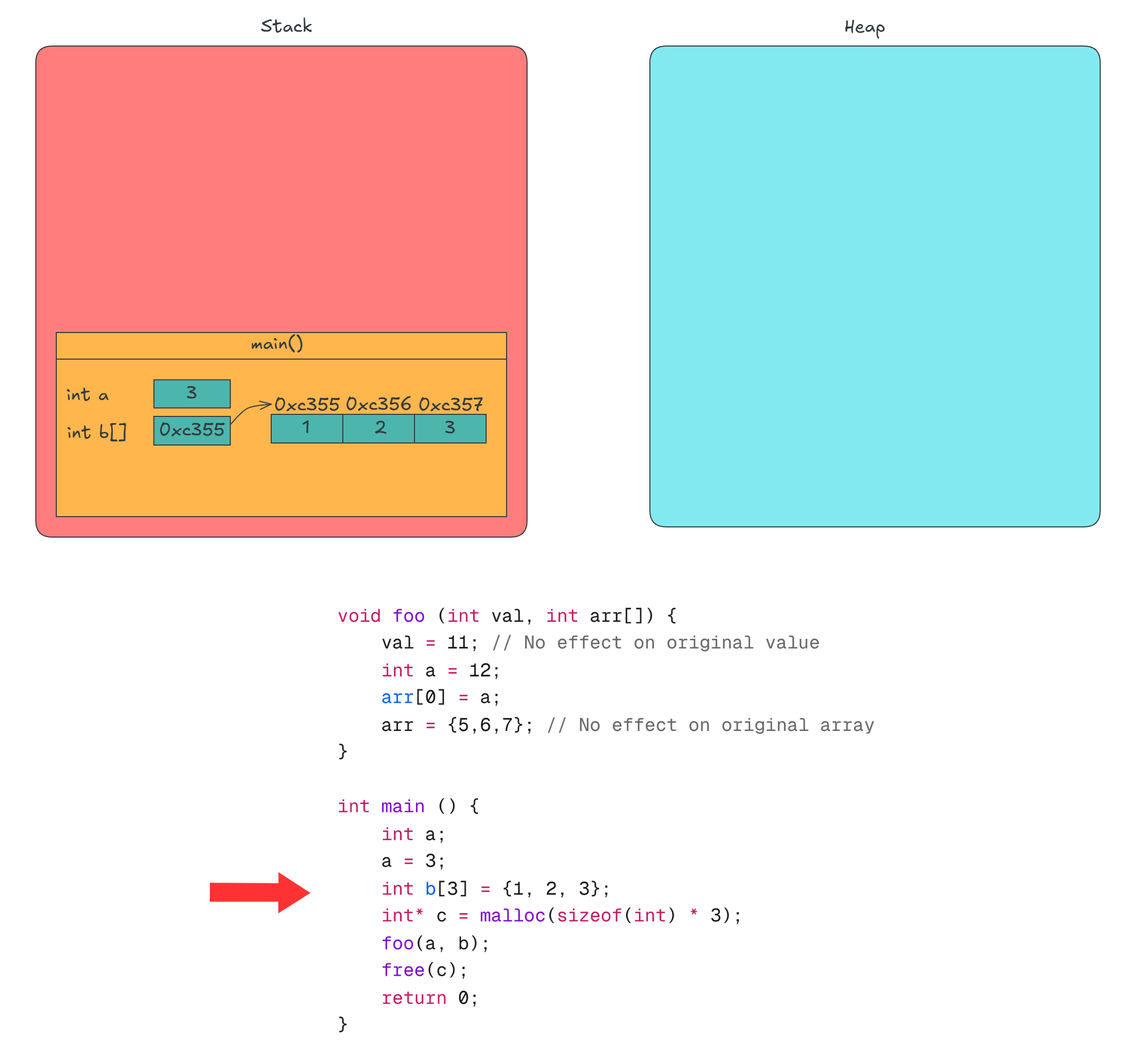

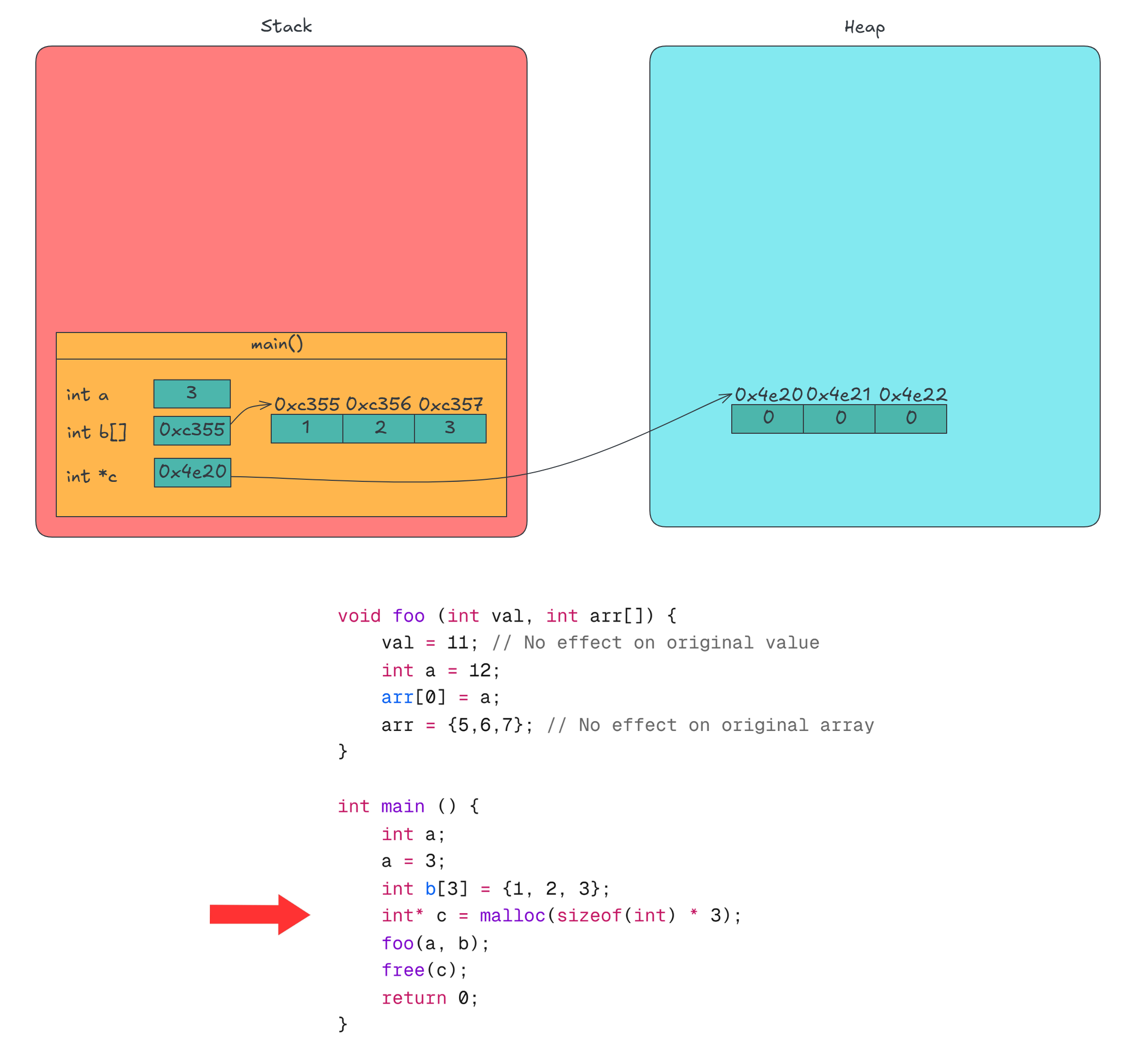

Before the function return statement, the stack will contain a and b, while c will store a pointer to the heap-allocated array.

Notice how every varabile has an address in memory, even a pointer which is essentially a container for a memory address, still has it’s own address.

Passing by value vs by reference

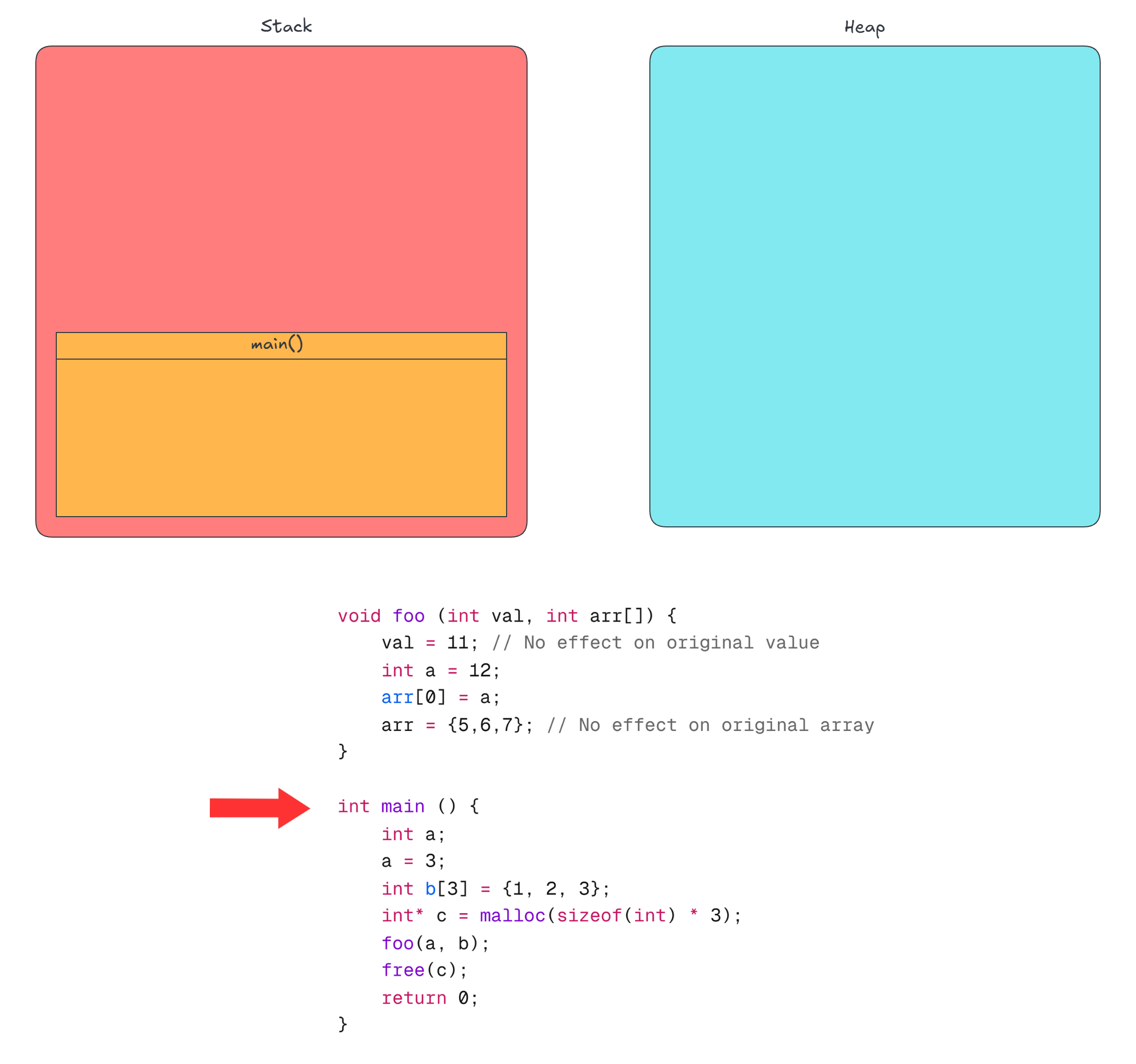

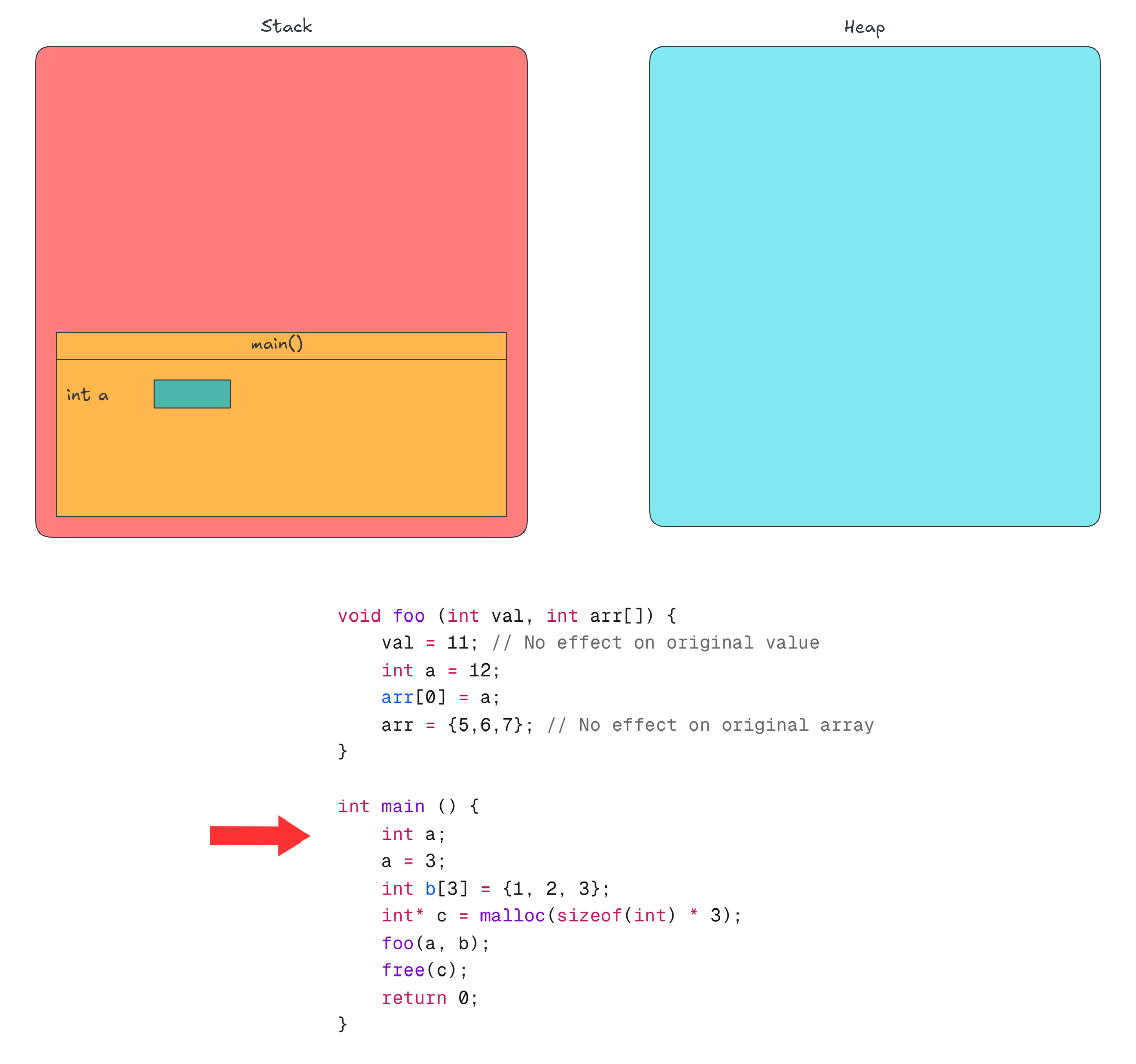

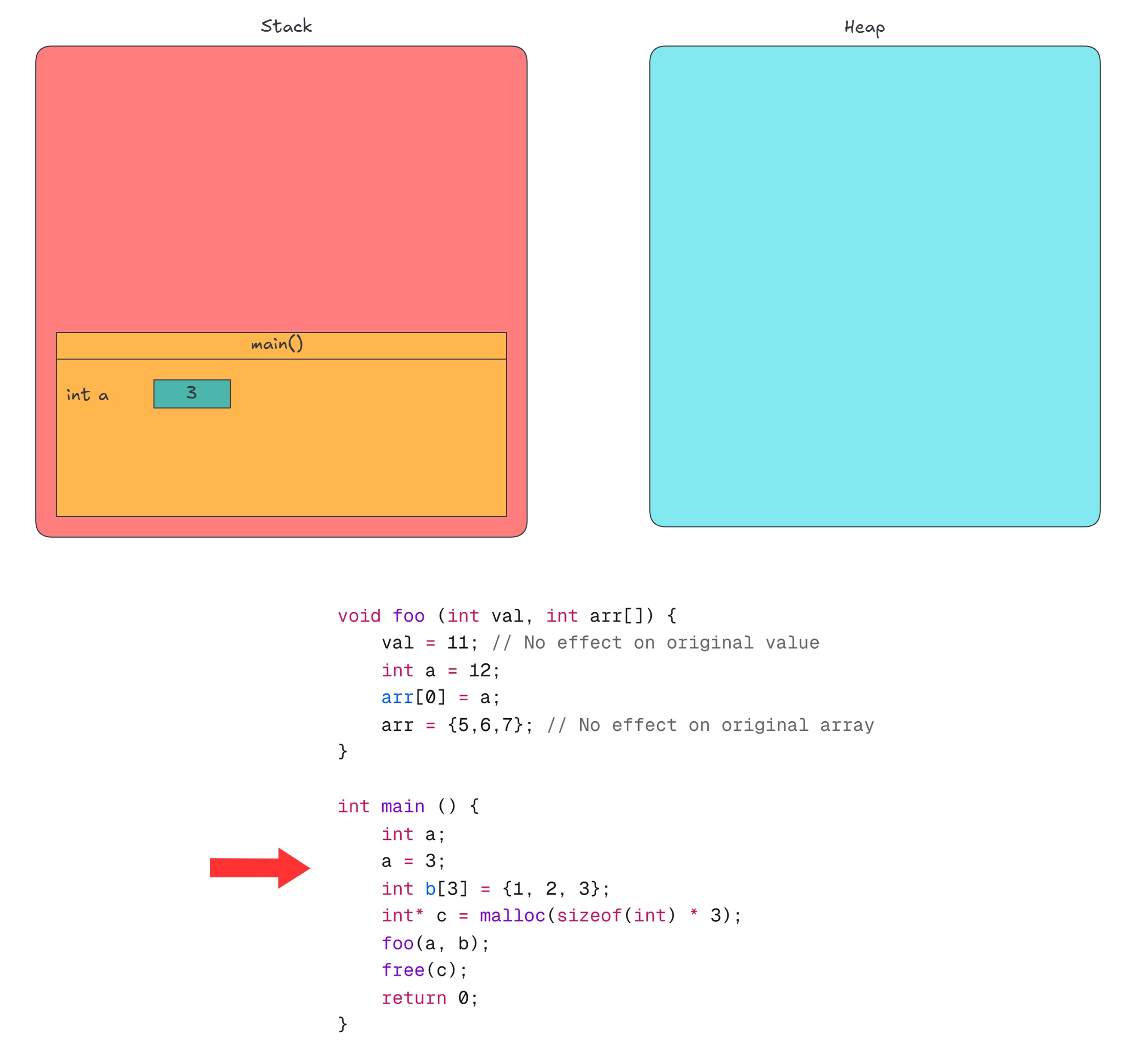

Let’s explore how function arguments behave when passed by value versus reference by taking this program as an example:

#include <stdio.h>

#include <stdlib.h>

void foo(int val, int arr[]) {

val = 11; // No effect on original value

int a = 12;

arr[0] = a; // Modifies the original array

arr = {5, 6, 7}; // No effect on original array

}

int main() {

int a = 3;

int b[3] = {1, 2, 3};

int *c = malloc(sizeof(int) * 3);

foo(a, b);

free(c);

return 0;

}

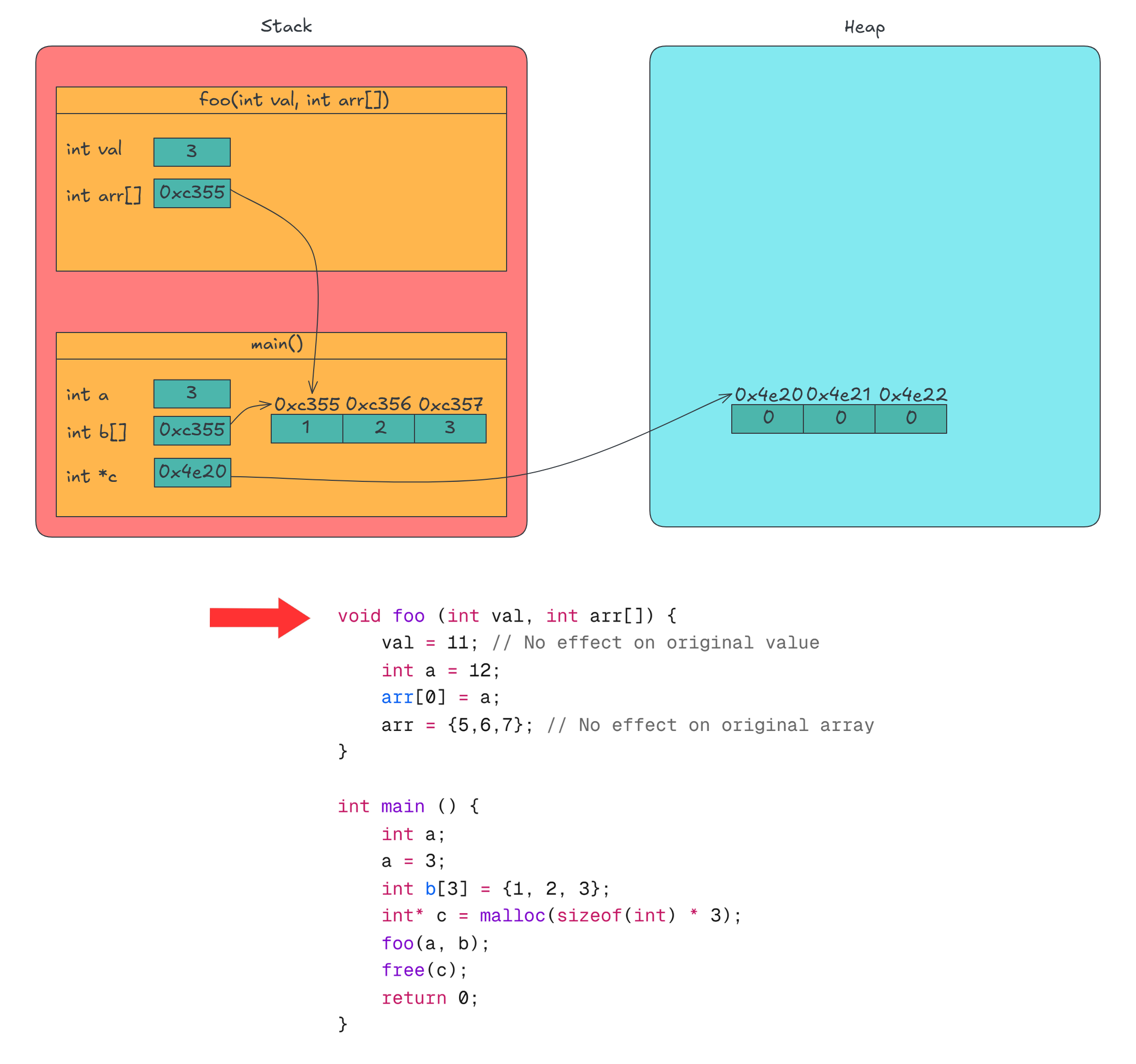

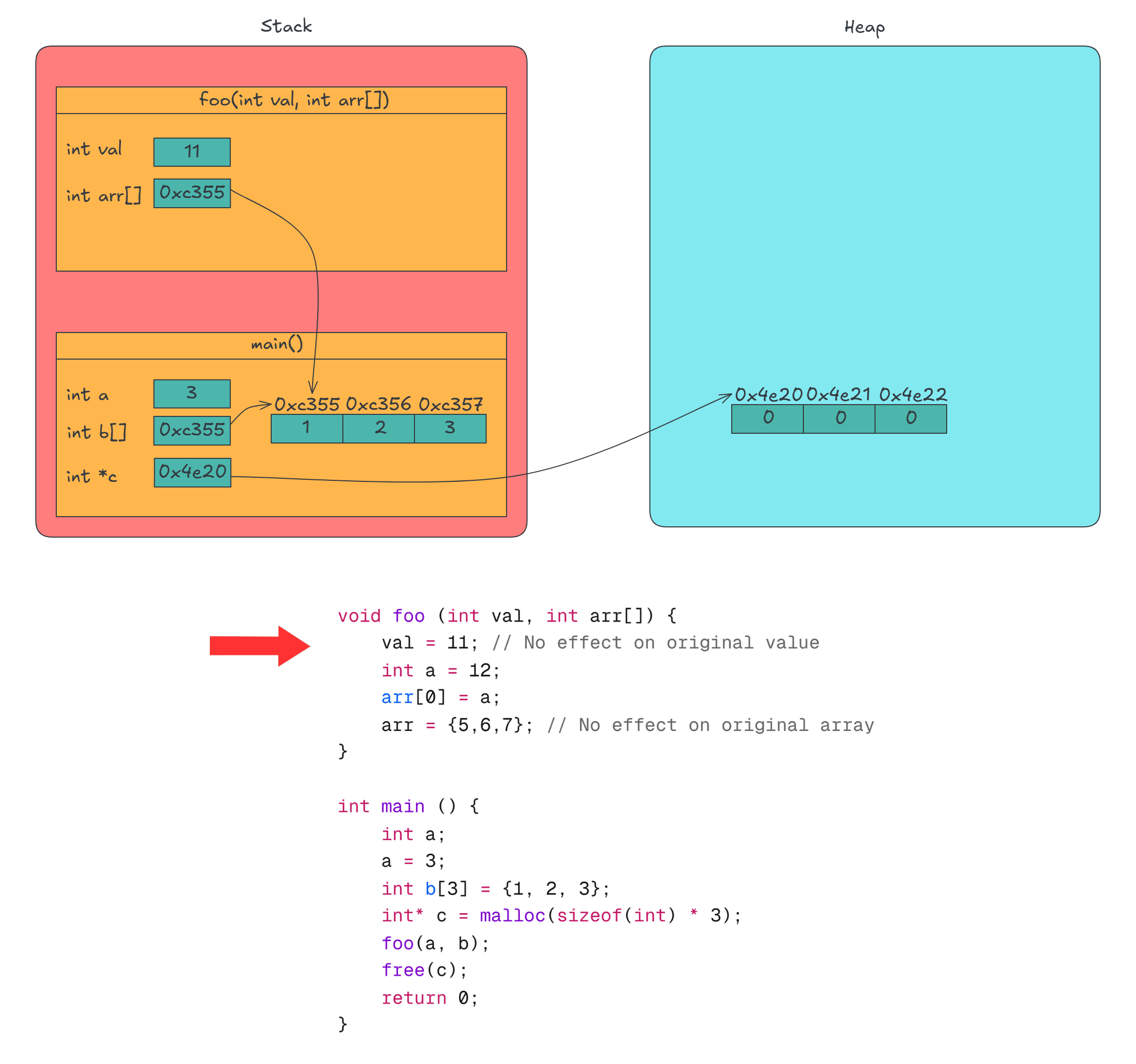

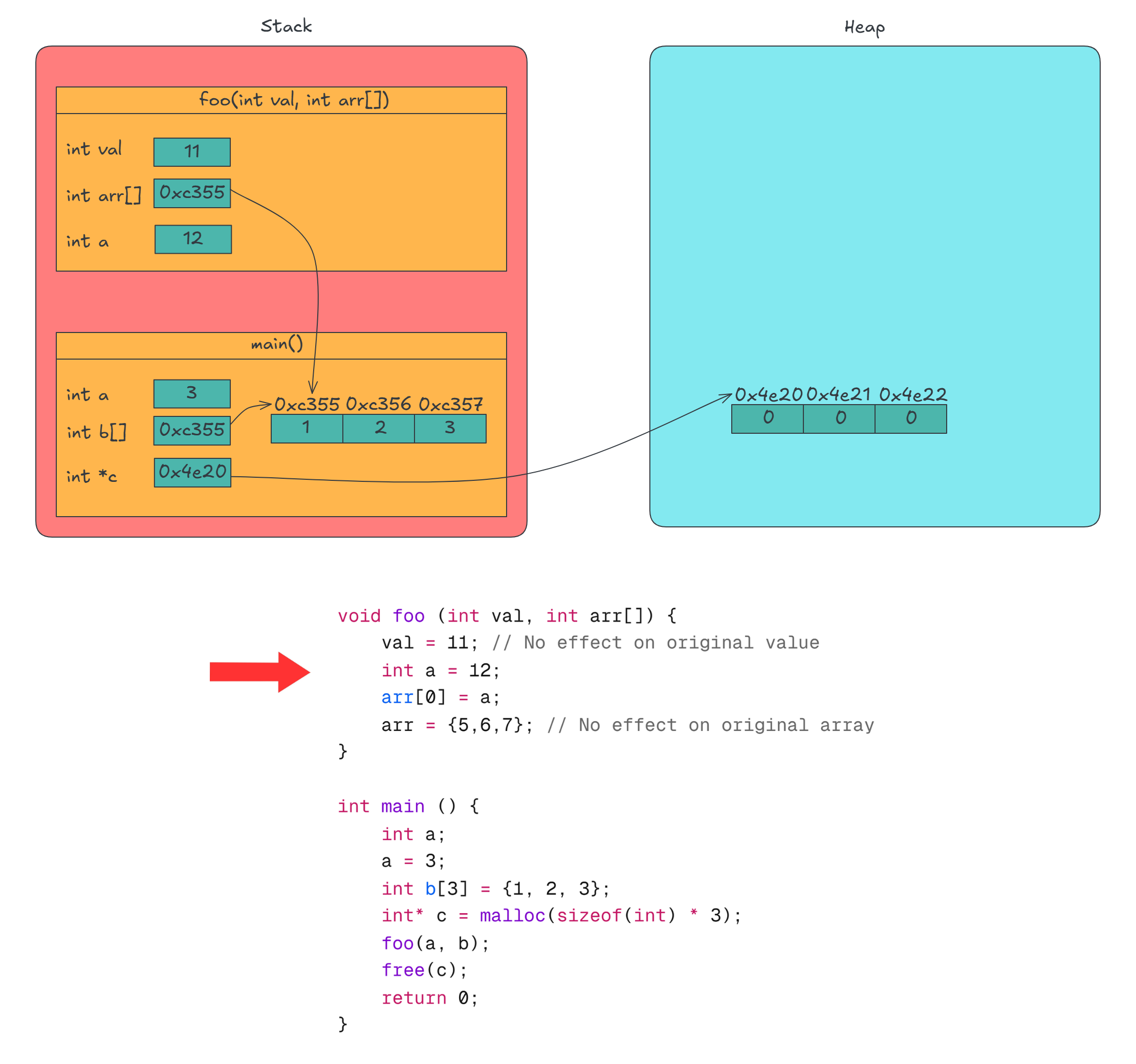

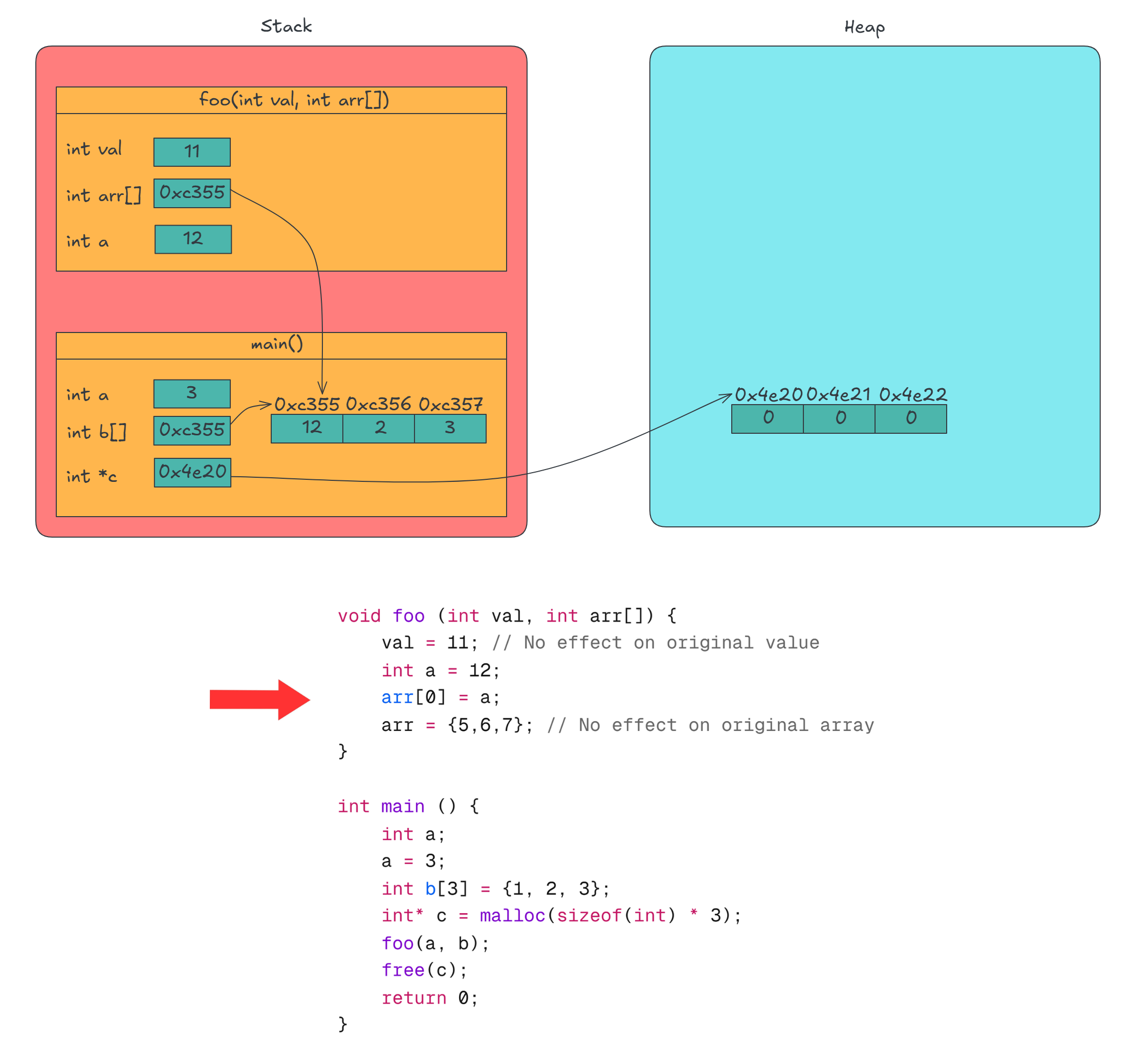

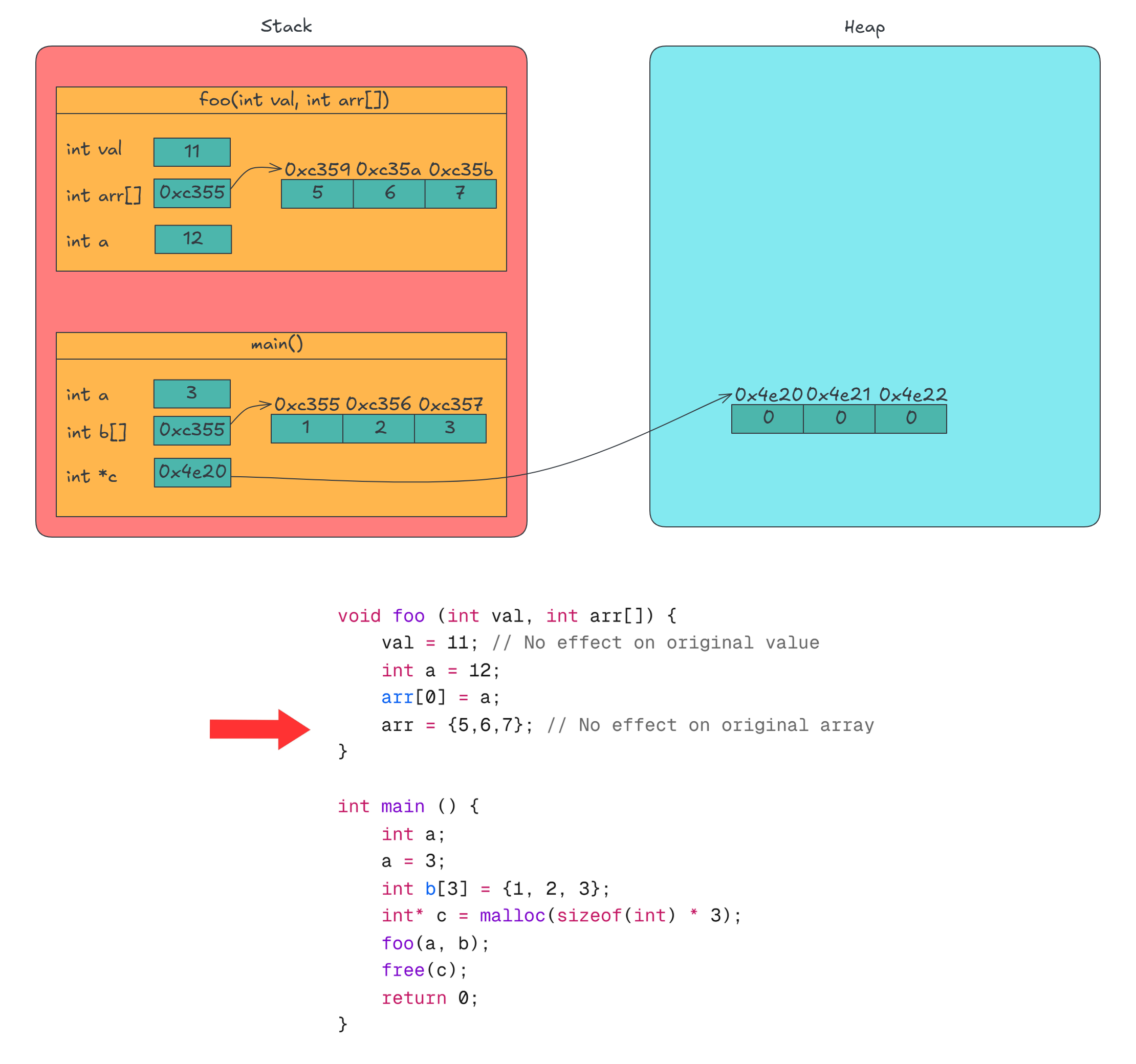

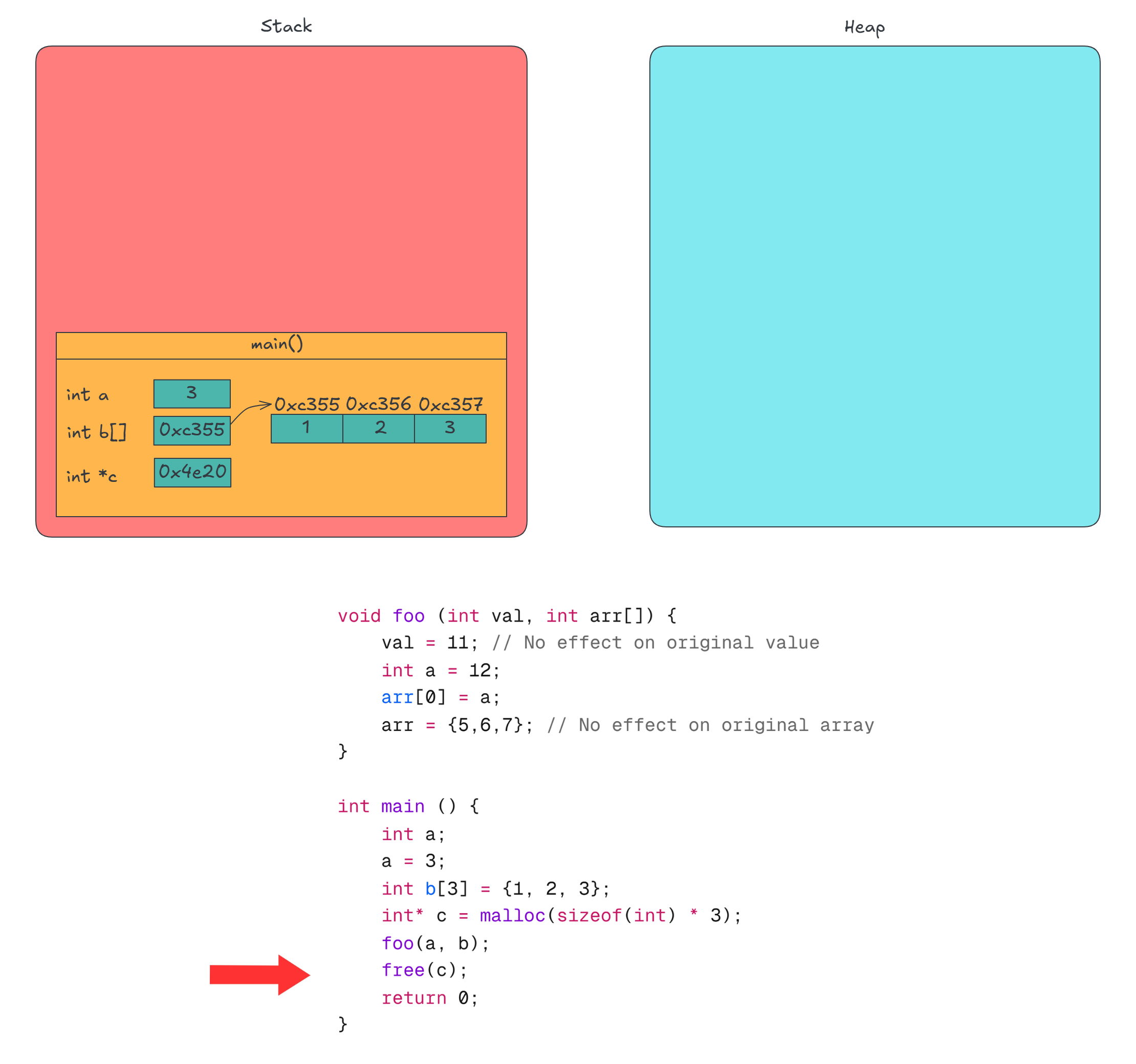

You can see what happens step by step here below:

The key takeaways are:

valis passed by value, meaning changes insidefoodon’t affectain main.arris passed as a pointer, so modifications toarr[0]affectb[0]in main.- Assigning

arrto a new array insidefoo()only changes the local copy of arr, not the original pointer.

Stack size and stack overflow

In Linux, you can check the stack size limit using:

ulimit -s

Or:

ulimit -a | grep "stack size"

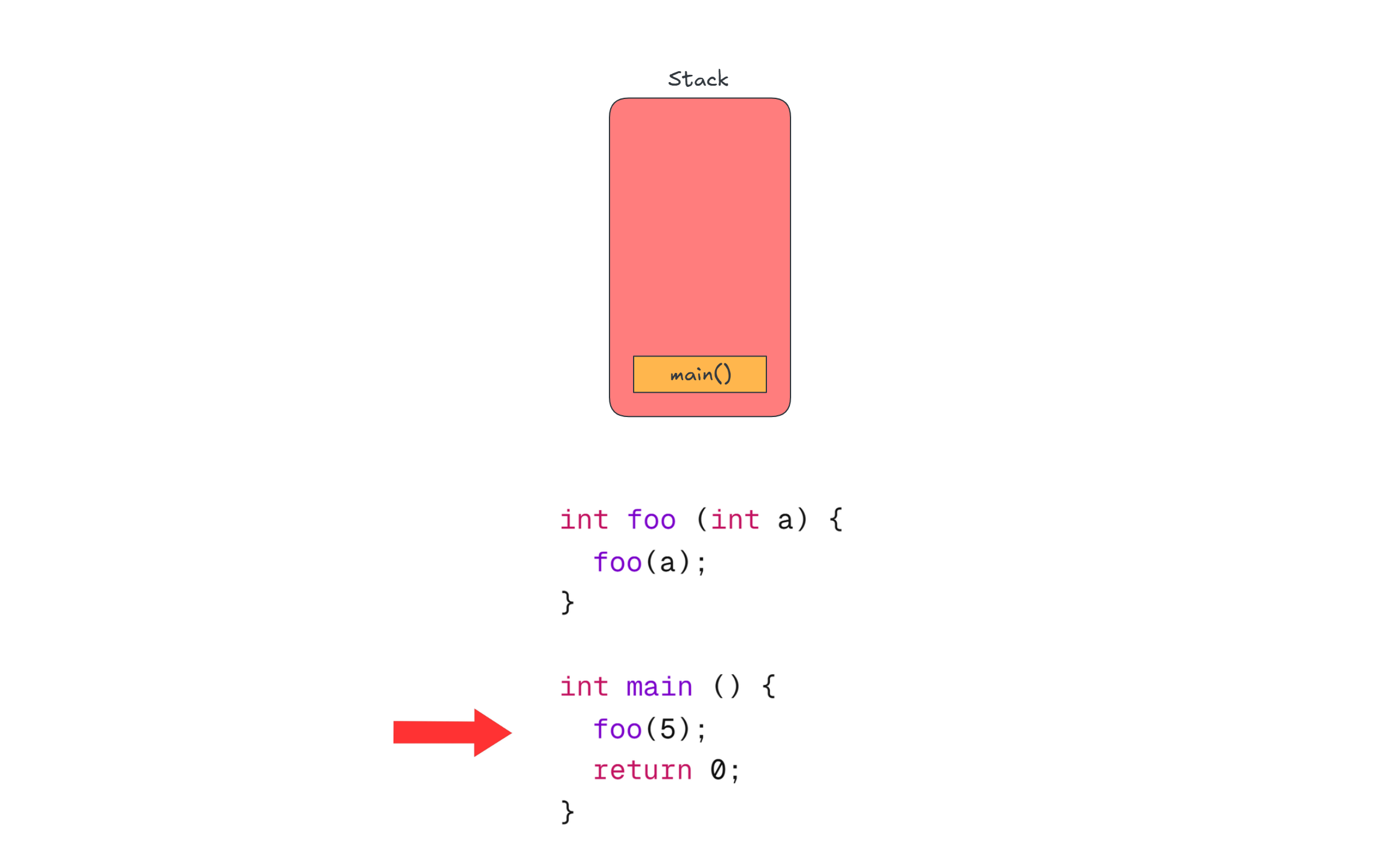

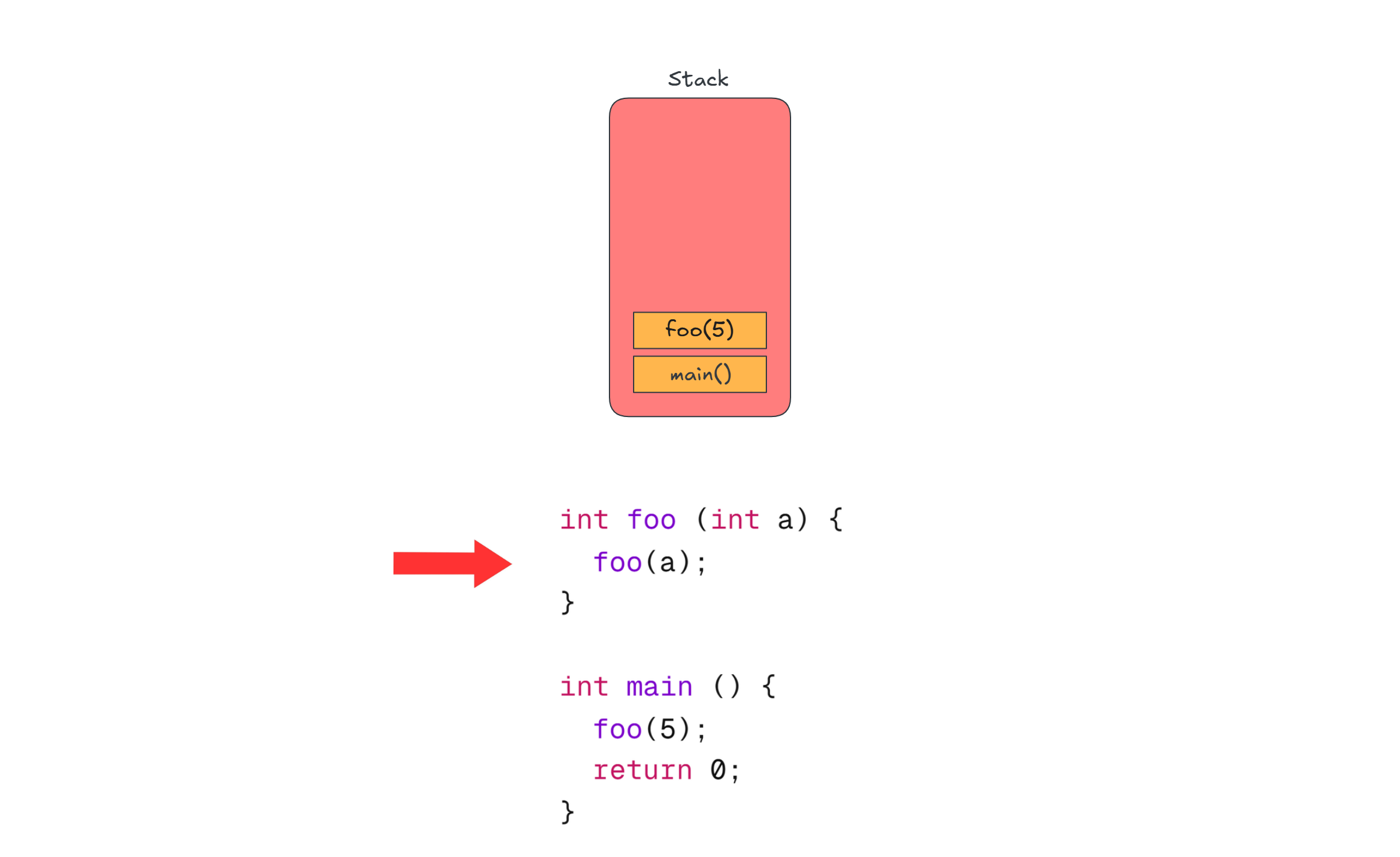

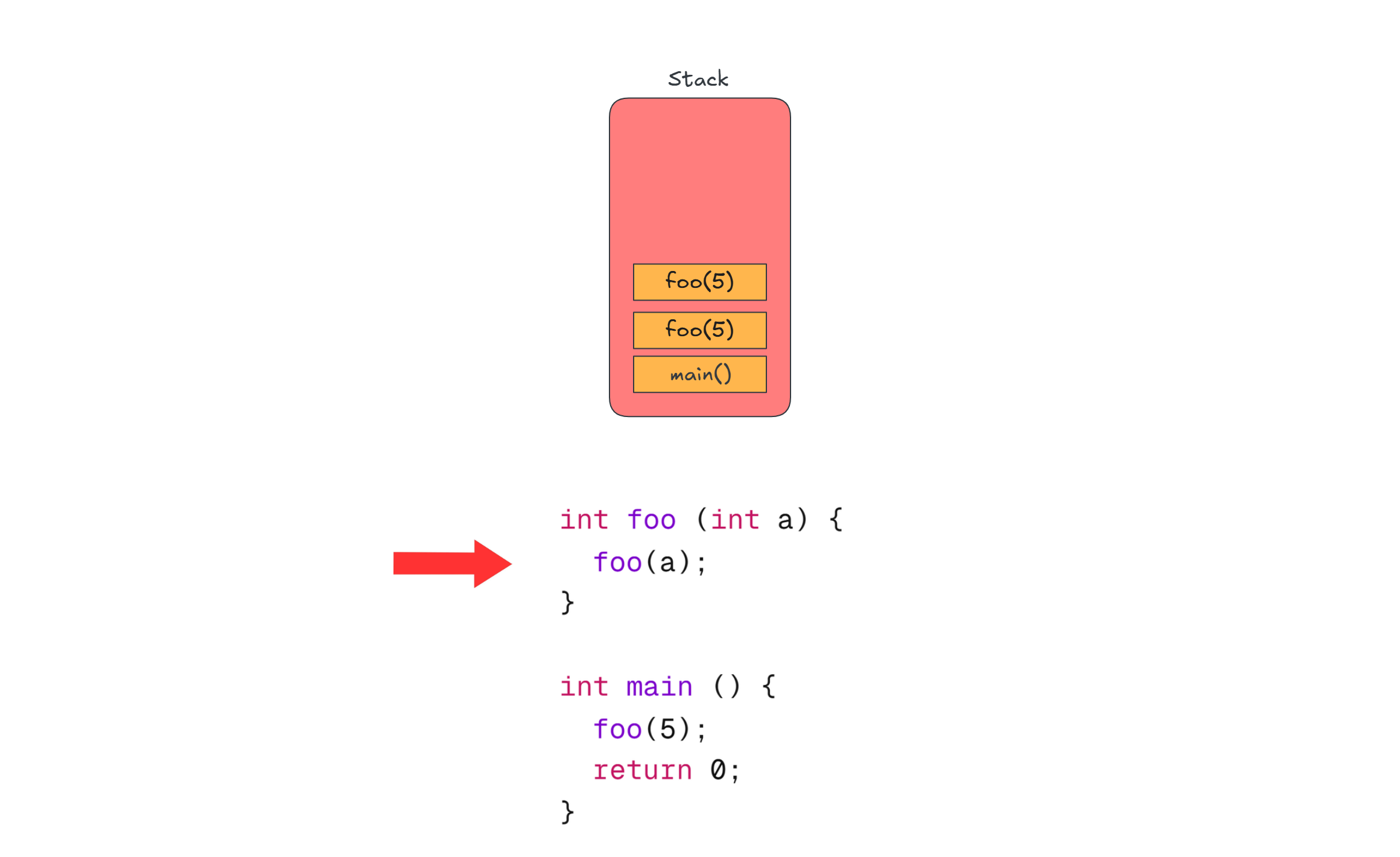

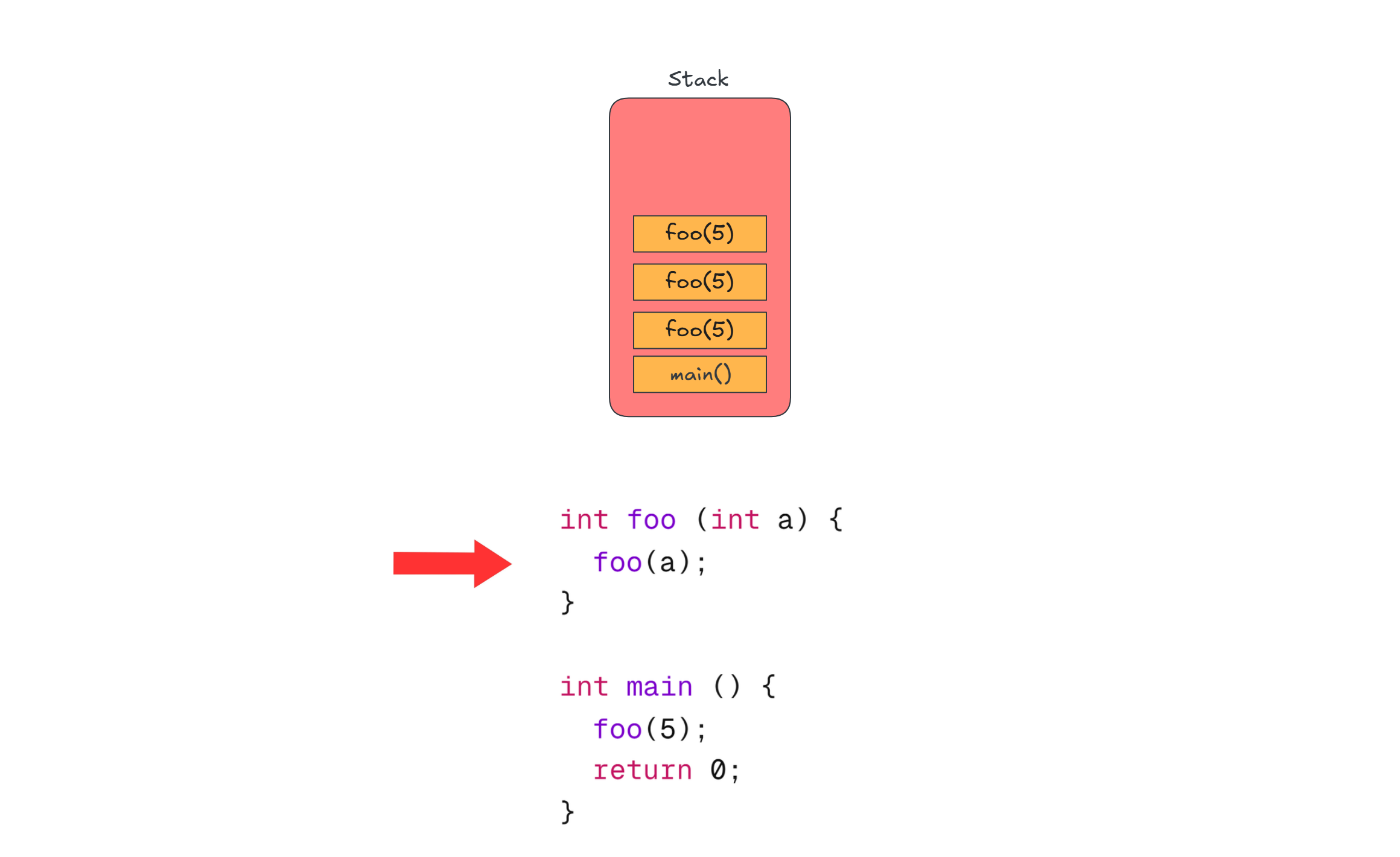

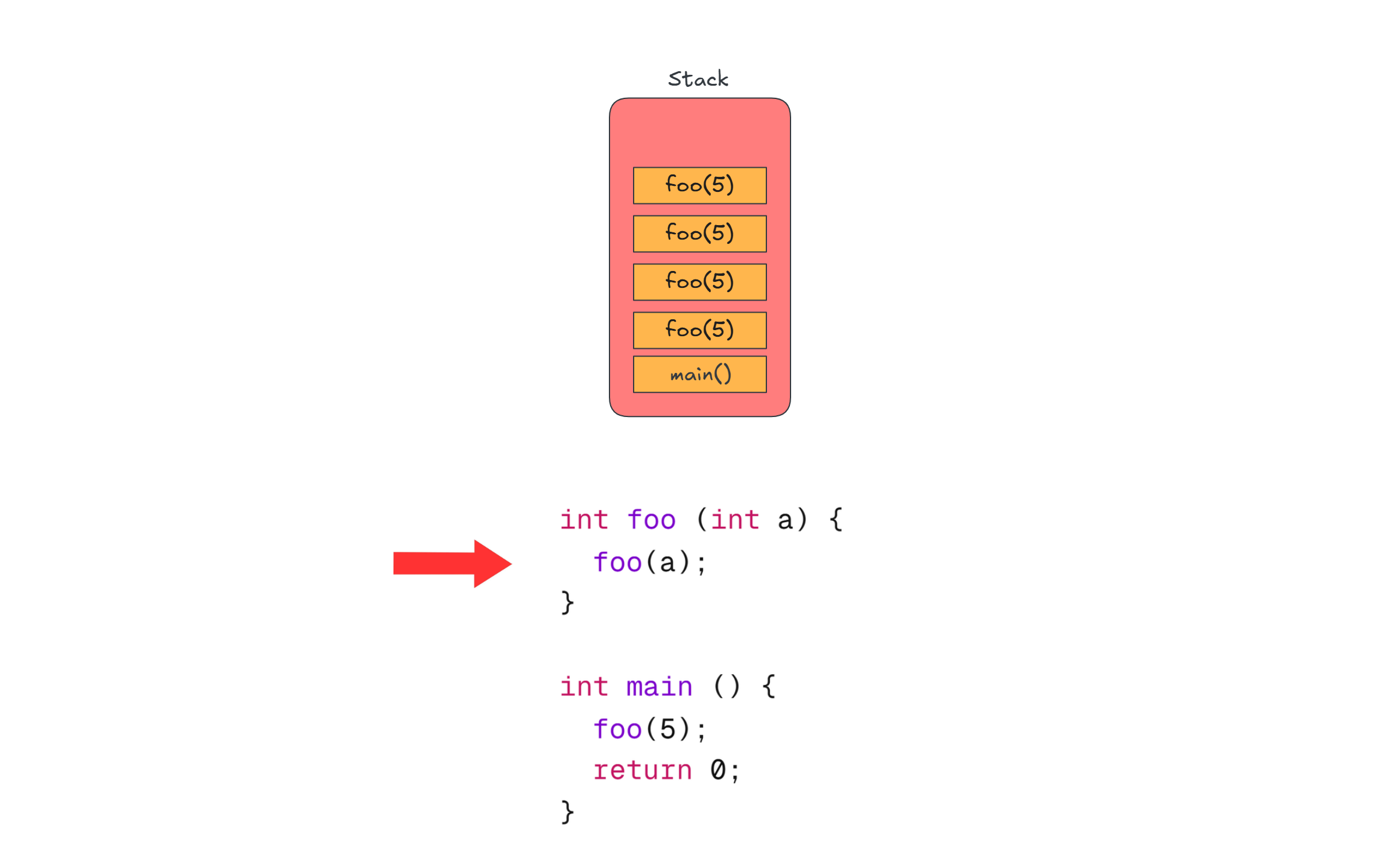

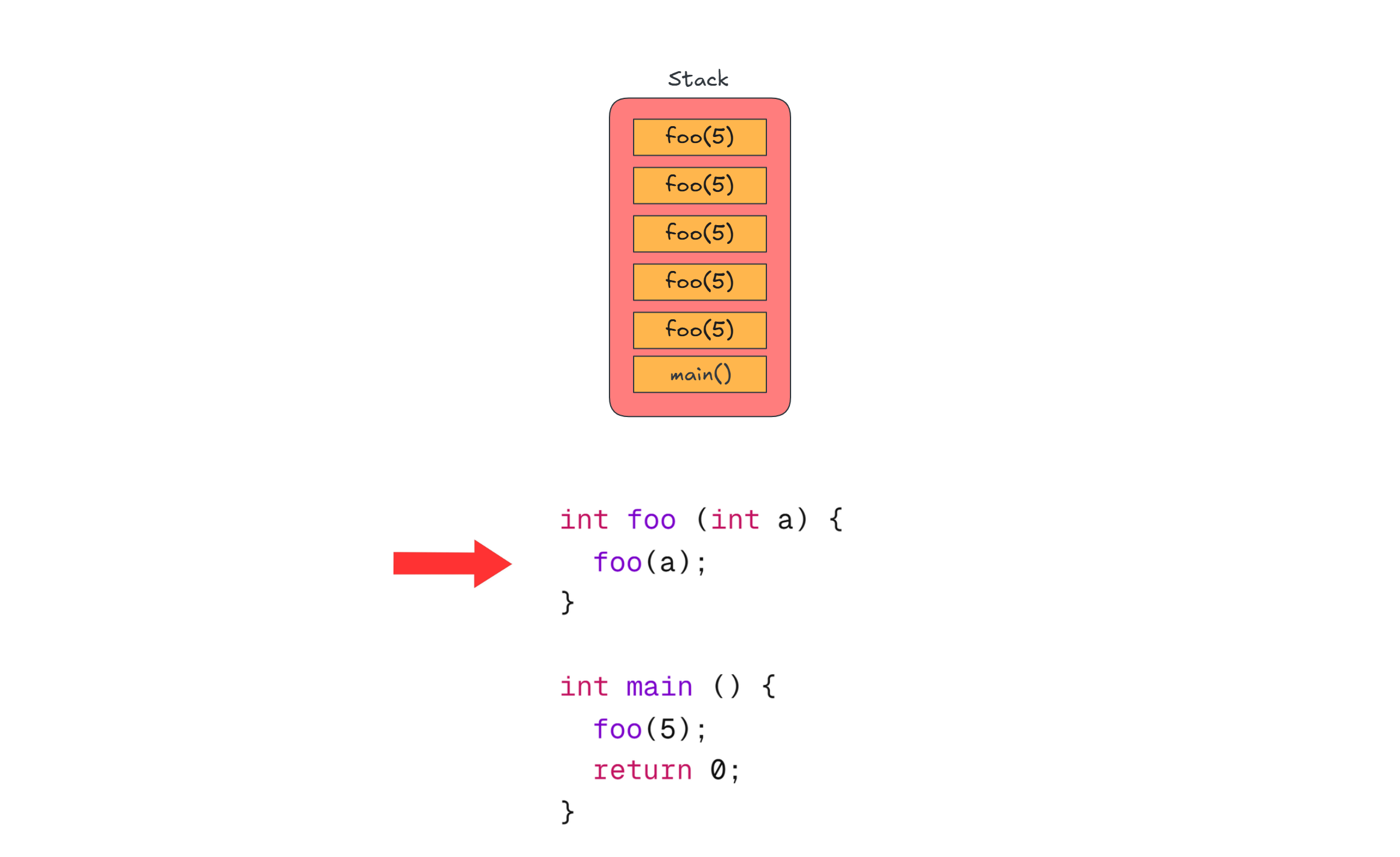

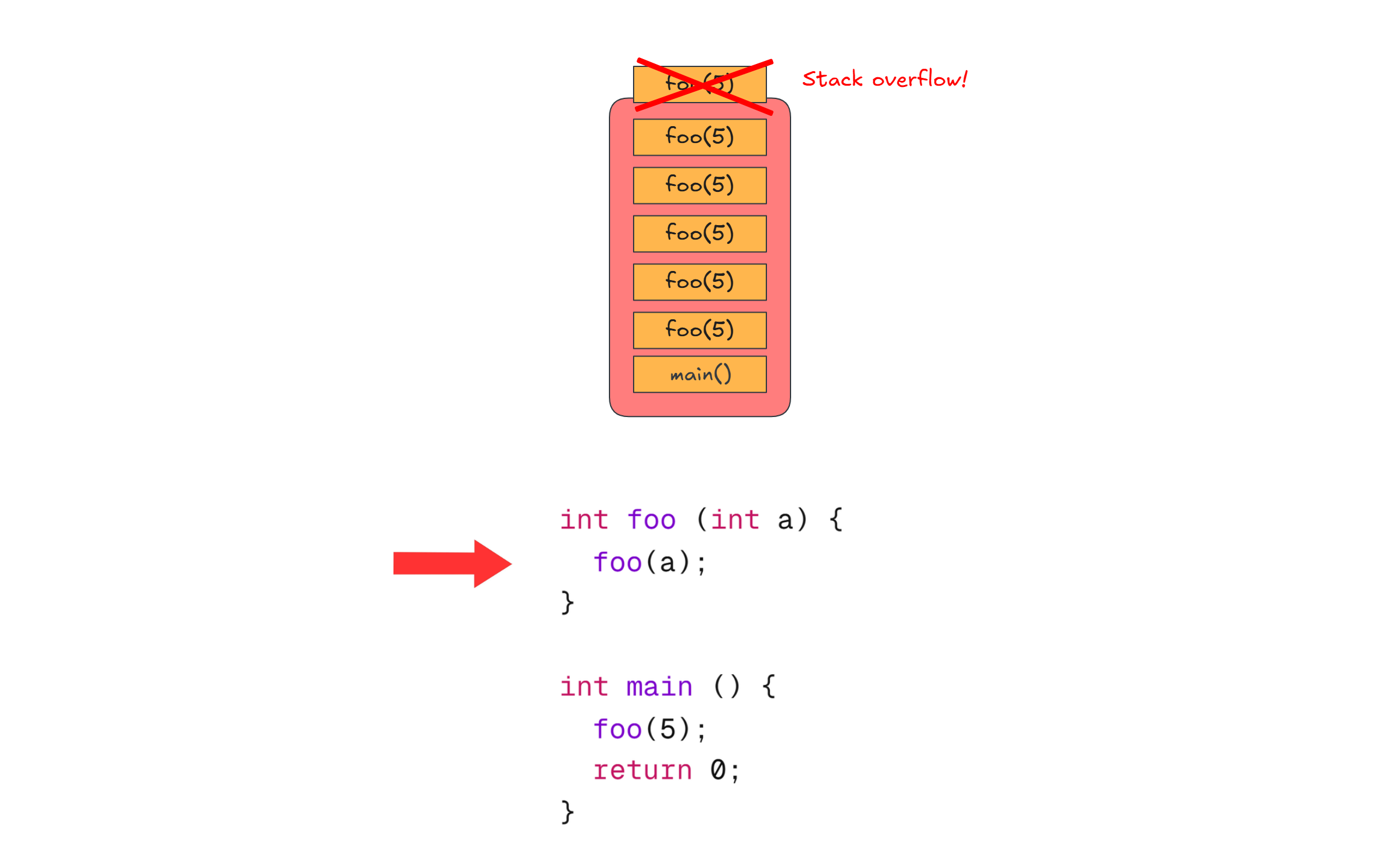

The stack has a fixed size, which explains why a stack overflow occurs when a function recurses indefinitely. Consider this example:

int foo (int a) {

foo(a);

}

int main () {

foo(5);

return 0;

}

You can already imagine from the carousel above what is happening, but here you go again:

References

- Online memory stack and heap visualizer (link)

Luigi